We can learn much from the way diplomacy was conducted in the Islamic courts of the southern Philippines, where the power of words to decisively and deliberately avoid conflict and regulate political relations was particularly prominent in border regions (thagr).

Since its origins, Islam aims at political expansion to the four corners of the ecumene, and therefore promotes a detailed order of an international law of nations (siyar) while Dār al-‘ahd (“Realm of the Pact”) refers to the domain where neither Muslims rule nor jihad is enforced.

Taking this into account, the historiography of Islam in the Philippines has centered rigorously on a ‘Dār al-ḥarb narrative’ of violence and conflict, and much influenced by César Majul’s concept of the “Moro Wars” to describe centuries of Philippine modern history and political and human relations. Recently, however, more attention has been given to the importance of Pacts (‘ahd) among the Philippine sultanates, in the form of Jawi letters, and the so-called Bichara as a way of political conduct. Bichara entails the performance of diplomatic and political interaction, negotiation, deliberation and communication, officially sanctioned by the sultanate court and religiously supervised by the Pandita (Islamic ritual specialists).

The Philippine sultanates, like most polities, maintained structured forms of governance to handle internal and foreign affairs, taxation, justice, religious practices and education. A variety of positions accommodated nobility and datus for social prestige. The royal residences, constructed from bamboo, nipa, and intricately carved wood, housed courts addressing important daily matters. Originating in a political vacuum beyond tribal structures, and faced with aggressive European imperial campaigns from the sixteenth century onward, diplomatic missions and correspondence emerged as an imperative tool for survival amidst building tensions and intensifying international competition. Consequently, the sultanates maintained diplomatic contacts with the Spanish administration in Manila and various other international parties and regional powers arriving in Sulu and Mindanao.

Over the course of more than three centuries, diplomatic processes further evolved and were formalized into protocols displayed at the court and transmitted through increasingly routinized written documents, missives and letters. Specific locations like Maimbung for Sulu and Sibuguey and Tamontaca for Maguindanao are frequently mentioned in Spanish sources, representing the seats of the sultans. A protocol of relations developed not only in dispatching letters, but also in the ceremonial aspects of embassies. Studying these enriches a neglected part of the sultanates’ history. Diplomacy aimed at equality among subjects, recognition, and assistance during internal or external troubles.

Malacca in particular served as a model for establishing Islamic polities in Southeast Asia, embodying religious legitimacy and cultural leadership. Aceh during the 16th and 17th centuries exemplified the sense of ‘Malayness’ and established a network of international support to counter European competitors. The successful model of Acehnese diplomatic practices was adopted by other sultanates, creating instruments to empower the state, defend autonomy, and formalize relations with other Islamic polities, notably the Ottoman Caliphate.

Concerning court protocol, the courts of Malay sultanates, resembling sumptuous Islamic courts, featured scribes, advisers, and wazirs, operating within the local context. Regardless the supposedly despotic or oligarchic system of government, the sultan was always surrounded by royal family members, advisers, and servants. In the case of Sulu, the sultan frequently consulted with the council of datus, especially during diplomatic engagements, where the palace served as the venue for receptions. These diplomatic encounters, carried out with greater or lesser formality, but with the same consequences as political acts, were known as “Bichara”, a Malay word for “talking”:

Bichara. Among the Mohammedans of the Far East, conversation held in official or simply informal meetings. ║ Friendly conversation of long duration. ║ Talk.

Word of positive historical value and essential to describe the vicissitudes of Spanish diplomacy with the Moros of Mindanao and Jolo. I found it for the first time, from the texts I have in my records, in a letter from the Governor of Malucas D. Jerónimo de Silva, dated in Ternate, July 31, 1612: “…he has already solved it [the king of Tidore] and so he does not want to entertain more bicharas in his kingdom” [...] Later, in a missive of Father Juan Barrios S. J., dated in Jolo, 1638 [...]: “After the King [of Jolo] had rested... they began the talks, or bichara, speaking in the manner of these people.”

Blumentritt, in one of his monographs, writes: “The conflicts between two datus or rancherías, are not solved at once by arms: the representatives or ambassadors of one side and the other celebrate long bicharas or conferences.”

It can, therefore, be stated that bichara is ‘diplomatic conversation.’ But the definition should not remain that way, because the conversations do not always reach that character: most of the times they do not go beyond informal. Almost all those held by the Spanish military with the magnates of Mindanao and Jolo should be described in no other way.

Bichara must have its origin in Malacca. It is curious the following text of the illustrious traveler Pedro Cubero Sebastian, he was in Malacca the year 1677. He was arrested and says: “He arrived on Friday, day of Bichara, which is the same as day of Council and, since I was called, I attended it (Retana, 1921: 53-54).

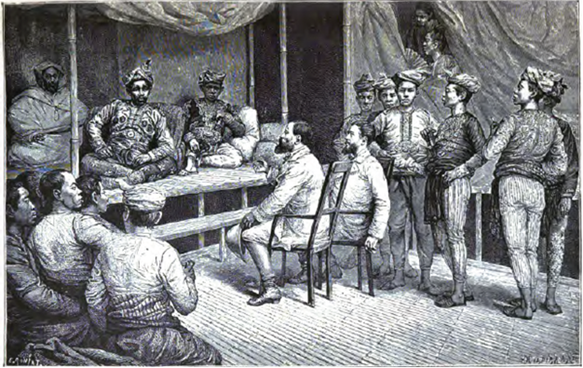

Thus, apart from an institution hosting regular meetings of the council of datus, the (ruma) bichara is also referred to as the (formal or informal) ‘diplomatic conversation’ in itself, that indeed derived from Malacca. The references that Retana quotes above also reveal the antiquity of the practice and its extension throughout Southeast Asia, from Malacca to Ternate. Above all, the bichara, should be seen as a platform for ‘diplomatic rendezvous’, entailing the means, processes and familiar forms of interaction between the parties. The main point of the bichara was the display of the sultanate, while the political goals of the negotiations were of secondary importance. An enlightening image of a bichara, reproduced by the French traveler Montano in 1886, has been preserved:

Here we can see the manner in which bichara was conducted, as a semi-formal occasion with the Sultan relaxedly seated on an upper level and the visitors positioned on chairs under the watchful eyes of the datus of the court. Accordingly, Montano wrote a vivid and detailed description of Maimbung, the palace and the reception, where this specific bichara took place. He mentions the eloquent Malay speech of sultan Jamāl al-A‘ẓam, the presence of the Raja Muda Badr al-Dīn, the hieratic foreign pandita, and the dynamics within the court of datus.

In sum, bichara was a about diplomatic performance. It helped integrating indigenous and Islamic laws within the conduct of politics, the use of words and the Arabic Adab (the whole of manners, education, behavior, beyond mere etiquette or savoir faire), in the complex, international political arena of Southeast Asian politics.

Isaac Donoso

Isaac Donoso is a professor at the University of Alicante.