Treaties with indigenous rulers formed the legal backbone underneath many empires, and the Dutch colonial empire in Indonesia was no exception. Hundreds and hundreds of treaties between the Dutch and numerous polities in Southeast Asia preserved in the colonial archives of the Dutch colonial state and its predecessor, the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie; VOC) testify to a long history of treaty-making. This year, I spend two months tracing these treaties in the national archives of Indonesia in Jakarta.

While many historians specialized in East-, South- and Southeast Asian history, have studied the treaties, particularly those of the VOC, as the VOC archives are very meticulous records on Asian history – in many cases the most detailed we have. However, previous historians often used transcripts and copies of original versions of these treaties, stored in The Hague, sometimes even in print. The VOC treaties were, for instance, transcribed and published by Dutch historians and archivists J.E. Heeres and F.W. Stapel (see here). 19th century treaties were also transcribed and copied, send to the Hague, where they were copied again, and after 1848 also included in the (now digitally available) colonial reports for the Dutch parliament.

I was looking particularly for the more exciting original versions of these treaties, which Heeres and Colenbrander, who worked in The Hague, probably never touched. Scattered through various state archival series, such as letters, reports and journals, I found hundreds and hundreds of them, spanning from the early seventeenth to the mid-twentieth century, concluded with powerful rulers such as the Sultans of Banten, Ternate or Palembang or smaller kings and lords in Gorontalo, Bali, and Timor.

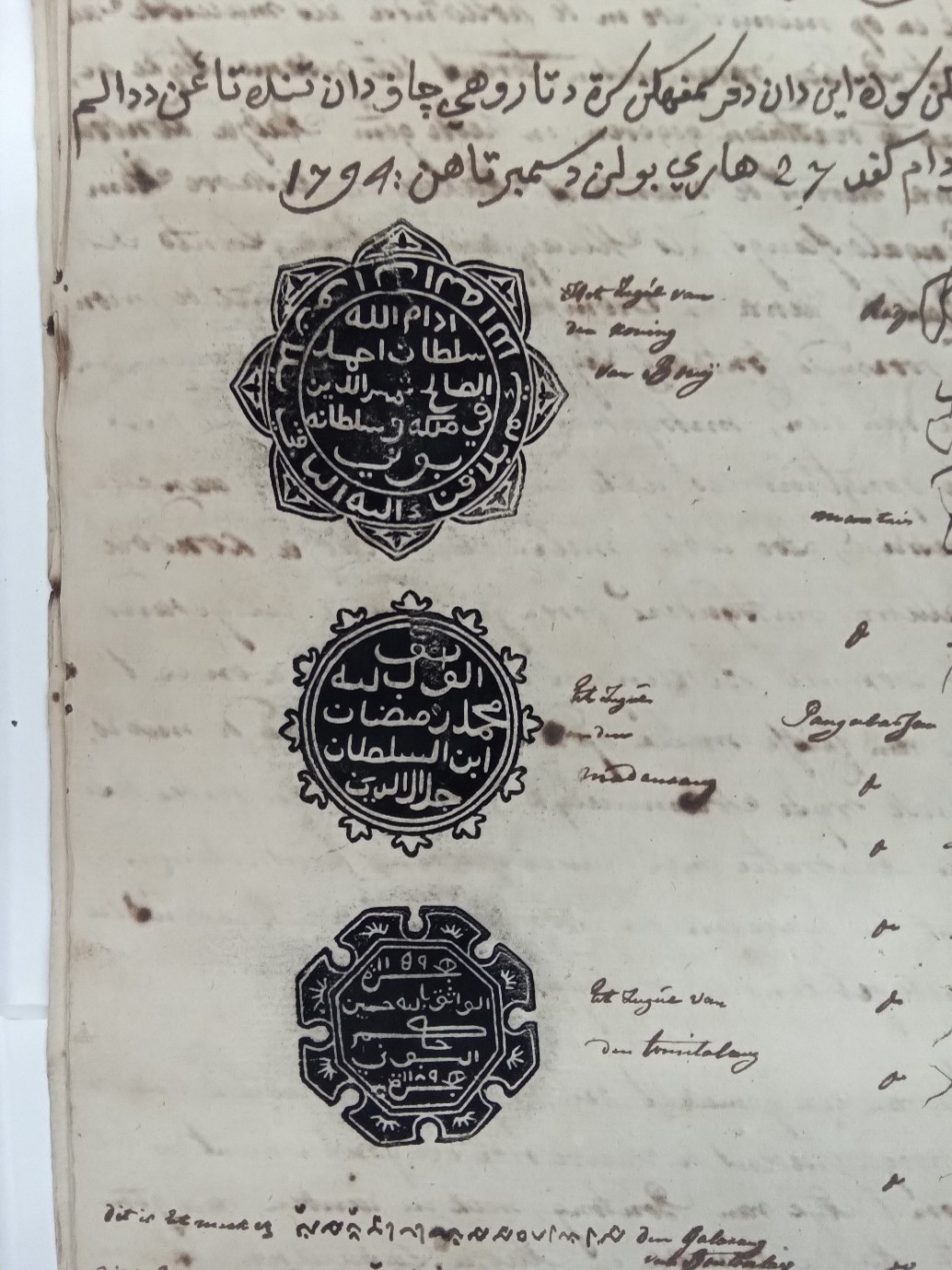

Such original treaties are very exciting to historians, because they display many things that transcripts and copies do not, such as the beautiful seals (see fig. 1) and signatures of indigenous rulers and princes. This tells us a lot about the people involved in the treaty-making process. Furthermore, the original treaties are always drafted in two or more languages – a European one (usually Dutch), an indigenous language (Javanese, Balinese, Buginese, etc.) and/or Malay in Jawi script. Comparing the original language to the translated versions may reveal quite some interesting discrepancies otherwise overlooked.

Fig. 1. Seals and signatures of the Sultan and princes of Bone on a contract with the VOC, 1794.

Fig. 1. Seals and signatures of the Sultan and princes of Bone on a contract with the VOC, 1794.

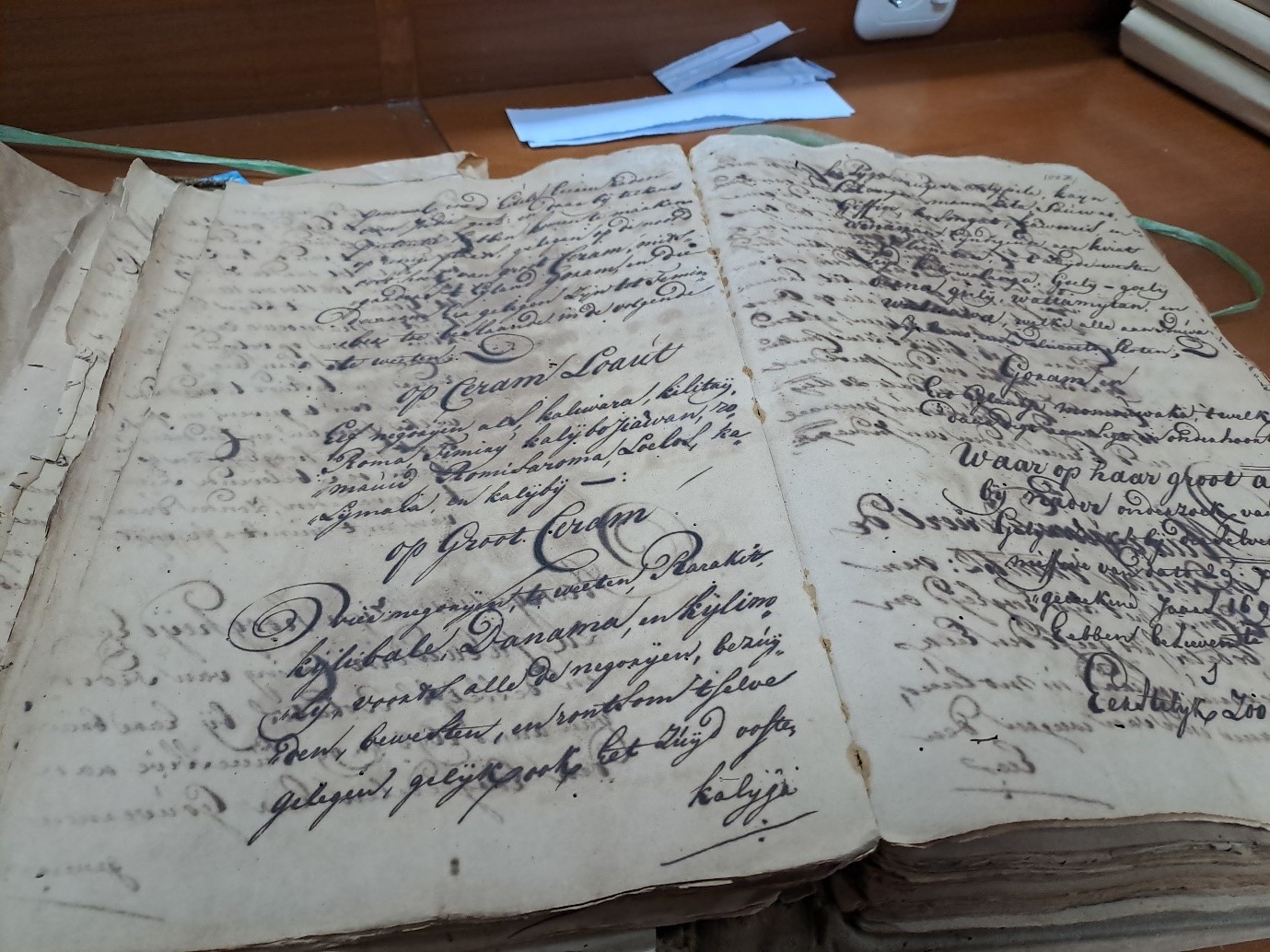

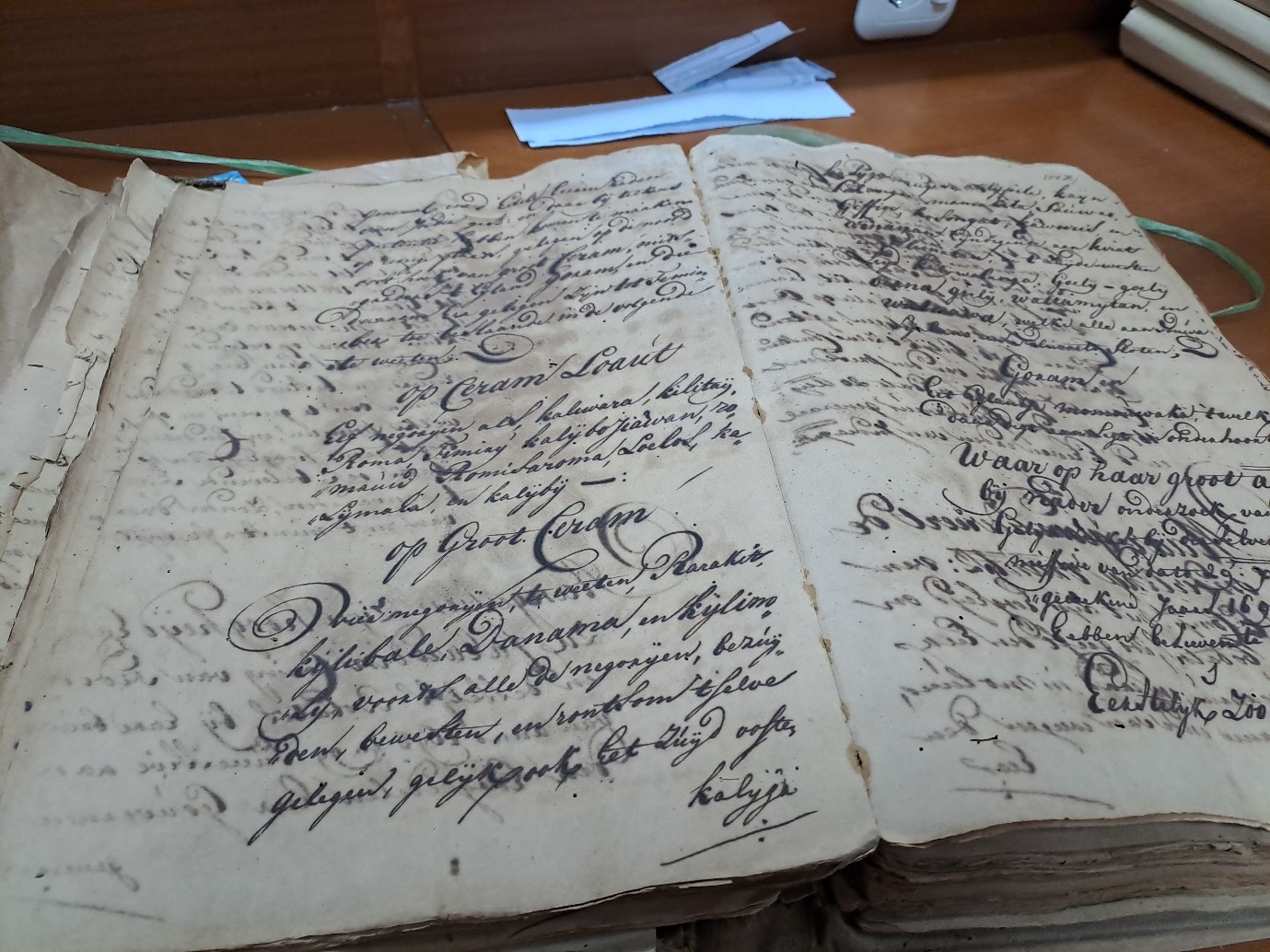

For instance, in many archival series, especially those from the ‘local’ or ‘provincial’ archives (gewestelijke archieven), we find series of treaties, in which succeeding rulers swear loyalty to the (expanding) terms of the old treaty (example). The treaties were always transcribed and copied numerous times, so that all relevant parties and institutes in Indonesia and the Netherlands obtained multiple copies of the text. Hence, we find quite some ‘copy contract books’ of specific regions related to specific years in the Indonesian archives (see fig. 2). The originals were also kept on the spot. In some keraton or palace archives in Indonesia, these have been preserved (see for instance here and here). Contract were also inserted into Resolution books of the Governor General in Batavia for VOC times, and in colonial times (post-1800), we find them in various archival series. Copies of these were also sent to the Netherlands, (see for example here).

Fig. 2. Contract book with copies of treaties between the VOC and Ternate, 1652-1743. ANRI Ternate 130.

Fig. 2. Contract book with copies of treaties between the VOC and Ternate, 1652-1743. ANRI Ternate 130.

While it may seem dull to look at multiple versions of the same document, studying them can tell a lot about the way these treaties were drafted, concluded, processed and stored. Furthermore, having different versions of the same document in different scripts may provide exciting new ways to train new Handwritten Text Recognition models and other forms of Artificial Intelligence that may help disclosing otherwise secluded structures in the archives.

Finally, the fact that the treaties were constantly copied of course also testifies to their importance. While it is unlikely that Southeast Asian rulers made wide use of written treaties before the arrival of Europeans in their region, by the nineteenth century it had become the standard format to conclude, maintain and negotiate foreign and colonial relations. Treaties and contracts became fundamental instruments in the Dutch colonial narrative of, first alliance formation, and often soon enough, imperial expansion. They supported the legalization of empire, and helped to subject kingdom after kingdom under vassalship of the Dutch first under a supposed ‘eternal friendship’ and ‘loyalty’, as vassals of the Dutch colonial state. They may teach us much about the processes underneath processes of indirect rule (governing colonial empires through local rulers and elites), negotiation and the administrative practices of colonial states.

Maarten Manse

Maarten Manse is a postdoctoral researcher at Linnaeus University and a member of the Historical Treaties of Southeast Asia research team.